AN OPEN PROPOSAL: Solar Democracy for Jamaica’s Post-Melissa Renewal; Distributed Solar for National Recovery and Trust

- aquest

- Jan 11

- 7 min read

A National Residential Rooftop Solar Transformation Programme for Jamaica

A Post-Melissa Resilience, Cost-of-Living, and Energy-Sovereignty Initiative

Submitted for consideration to:

The Government of Jamaica (GOJ)

Office of the Prime Minister

Cabinet of Jamaica

Prepared by:

Dennis A. Minott, PhD

© Dennis A. Minott, PhD. All rights reserved.

No part of this document may be reproduced, stored, transmitted, or adapted in any form without prior written permission of the author, except for brief quotations with full attribution.

IMAGE 1: Residents walk through Lacovia Tombstone, Jamaica, in the aftermath of Hurricane Melissa, Wednesday, Oct. 29, 2025. |Matias Delacroix/AP VS. IMAGE 2: A damaged home in Treasure Beach, Jamaica, following Hurricane Melissa. Its solar panels survived. | Abbie Townsend / The New York Times

Executive Summary

Jamaica now faces a convergence of challenges and opportunity: escalating electricity costs, climate-intensified storms such as Hurricane Melissa, fragile centralized infrastructure, and rising public intolerance for opaque, extraction-driven economic models. At the same time, international experience—most notably India’s recent residential rooftop solar expansion—demonstrates that well-designed public policy can rapidly democratise clean energy while strengthening national resilience and household finances.

This proposal recommends the establishment of a National Residential Rooftop Solar Transformation Programme (NRRSTP)—a Jamaican-scale analogue of India’s

प्रधान मंत्री सूर्य घर योजना .

Pradhan Mantri Surya Ghar Yojana—anchored by a dedicated Ministry of New and Renewable Energy. The programme would enable tens of thousands of Jamaican households to adopt rooftop solar (with optional battery storage), lower electricity bills, reduce fuel imports, and enhance disaster resilience, while explicitly rejecting billioneering, rent-seeking, and monopolistic capture.

This is not an ideological exercise. It is a pragmatic, time-bound, fiscally disciplined national response to a post-Melissa reality.

Context and Rationale

Hurricane Melissa once again exposed Jamaica’s vulnerability to centralized electricity generation and long transmission corridors. Grid failure, prolonged outages, and cascading economic losses are now predictable features of each major storm season. Meanwhile, household electricity costs remain among the highest burdens on Jamaican family budgets.

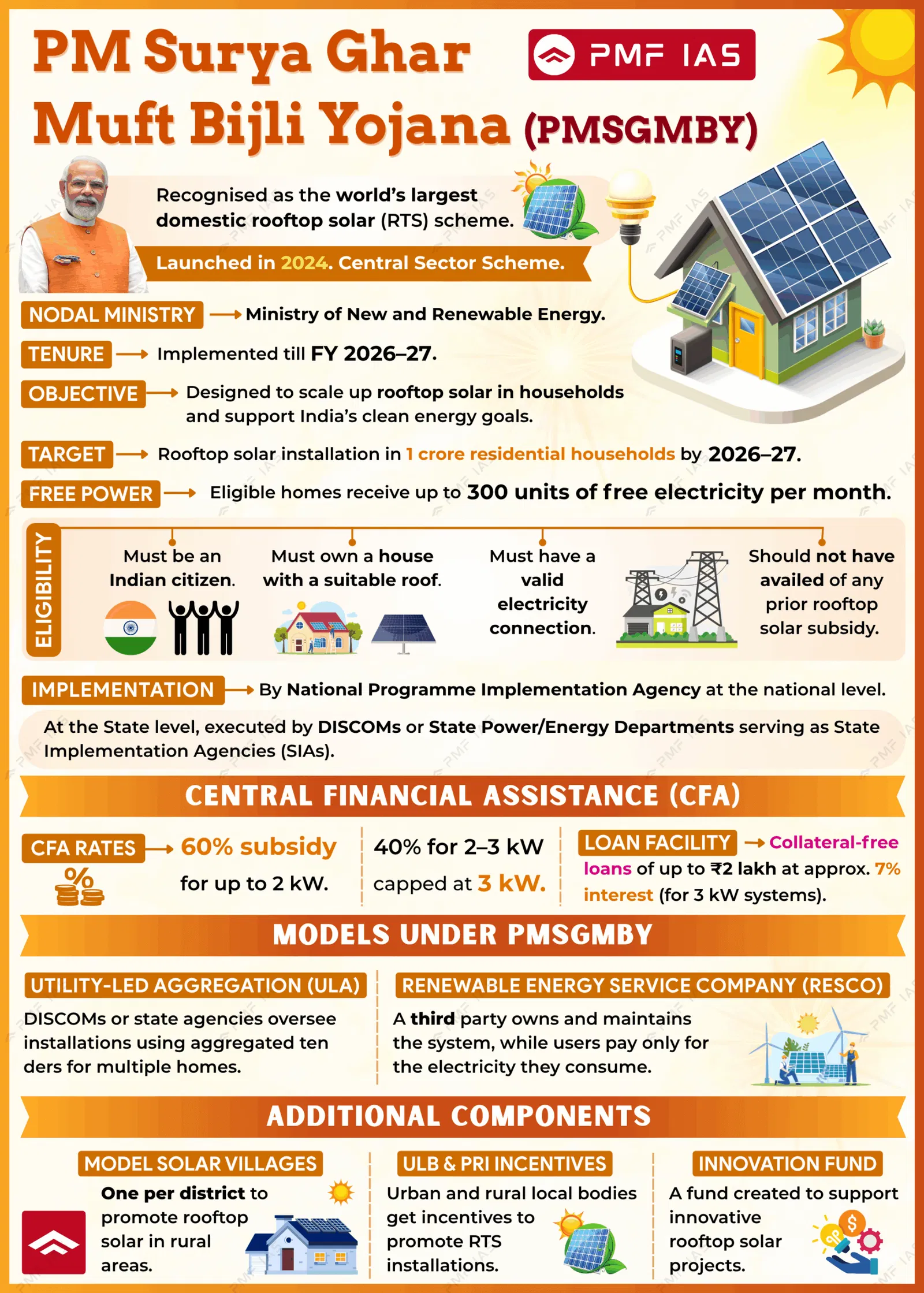

IMAGE 1 & 2: Designed to scale up rooftop solar in households and support India’s clean energy goals, these are posters describing India's 'PM Surya Ghar Muft Bijli Yojana', launched in 2024, and to be implemented throughout fiscal years 2023-24 to 2026-27.

International evidence is instructive. India’s recent residential rooftop solar programme mobilised millions of households by combining capital subsidies, simplified procedures, and public-interest oversight, achieving gigawatt-scale deployment in under two years. Jamaica need not replicate India’s scale—but it can replicate its policy logic, adapted to our geography, grid, income distribution, and hurricane exposure.

Crucially, Jamaica must do so without repeating the historical errors of over-centralisation, discretionary licensing, or opaque procurement that have undermined public trust in other sectors.

© Dennis A. Minott, PhD. All rights reserved.

No part of this document may be reproduced, stored, transmitted, or adapted in any form without prior written permission of the author, except for brief quotations with full attribution.

Vision Statement

A Jamaica in which households are producers as well as consumers of energy; where solar rooftops strengthen national resilience, lower living costs, and reduce import dependence; and where renewable energy policy is governed transparently, equitably, and free from billioneering.

Core Programme Objectives (Five-Year Horizon)

Install residential rooftop solar systems on at least 200,000 Jamaican homes, prioritising owner-occupied dwellings and hurricane-exposed communities.

Add approximately 1 GW of distributed solar capacity, reducing peak demand stress on the national grid.

Reduce participating household electricity bills by 30–50 percent, improving disposable income and economic stability.

Enhance post-storm energy resilience, particularly for refrigeration, communications, water pumping, and medical needs.

Create a domestic solar workforce and service ecosystem, generating skilled employment across all parishes.

Programme Design Pillars

1. Upfront Cost Reduction and Fair Financing

High upfront costs remain the single greatest barrier to residential solar adoption.

The NRRSTP would therefore provide:

Capital grants covering up to 40 percent of system cost for eligible households.

Concessionary financing, supported by government guarantees, offered through regulated financial institutions.

Duty-free and zero-GCT treatment for certified solar panels, inverters, batteries, and mounting systems.

All incentives will be technology-neutral within safety standards and transparent in allocation, with published criteria and caps.

IMAGE 1: 24/7 Repair and Maintenance services at Carisol Solar Systems & IMAGE 2: Solar Systems available for Residential, or Commercial Needs quoted at Carisol Group

If households can carry phones, water, and medicine through storms—why shouldn’t policy help them?

2. Single-Window Access and Administrative Simplicity

To avoid procedural bottlenecks:

A national online portal will manage applications, approvals, installer assignment, and grant disbursement.

Time-bound approvals (e.g., 30 days maximum) will apply to permitting and grid interconnection.

Installers will be pre-qualified based on competence, insurance, and consumer-protection standards, not political access.

3. Solar-Plus-Resilience Integration

Given Jamaica’s hurricane exposure, the programme will:

Encourage solar-plus-battery configurations through enhanced incentives.

Mandate hurricane-rated mounting and electrical standards.

Support rapid post-storm inspection and recommissioning teams trained under the programme.

Solar under this initiative is not merely about decarbonisation; it is about keeping lights, refrigeration, and communications on when the grid fails.

4. Public Awareness and Community Trust

A national education campaign will:

Explain realistic costs, savings, and maintenance obligations.

Use parish-level demonstration sites.

Partner with schools, churches, and community groups to normalise solar literacy.

Public trust is a technical asset. Without it, even generous incentives underperform.

5. Labour Development and Local Value Creation

The programme will:

Establish certified training pathways for installers, electricians, inspectors, and maintenance technicians.

Encourage local assembly and service enterprises where economically viable.

Ensure labour standards and safety compliance.

Governance Framework: Ministry of New and Renewable Energy

The scale and cross-cutting nature of this initiative require a dedicated Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, distinct from fossil-fuel legacy mandates.

Ministerial Appointment Standard

The post should be filled by a politically astute Permanent Secretary–level professional or an equivalent senior business or academic leader, with a demonstrated record of ethical leadership, administrative competence, and public trust — whether drawn from among JLP-supporter initials (ALH, CNWN, BCS, RD, RC, StW, PM1, WP, DD2, HC, CZ) or PNP-supporter initials (DF, DD1, BB1, DB, PM, MT, FJ, PP, TB, EC, QM, GJ, KW, NM), provided always that the overriding qualification is integrity, national service, and an unambiguous commitment to transparency and the public good.

This framing explicitly places competence above partisanship, while recognising Jamaica’s political realities.

Minister of New and Renewable Energy: Role Summary

![Renewable energy distribution across the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) nations. MAP created based on data from Ochs et al. [19]. Image Credit: RESEARCHGATE : Brecha, R.J. & Schoenenberger, Katherine & Ashtine, Masaō & Koon Koon, Randy. (2021). Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion—Flexible Enabling Technology for Variable Renewable Energy Integration in the Caribbean. Energies. 14. 2192. 10.3390/en14082192.](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/331ac9_3562faa11b384546a84d043b7d30e1c0~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_850,h_496,al_c,q_90,enc_avif,quality_auto/331ac9_3562faa11b384546a84d043b7d30e1c0~mv2.png)

The Minister shall:

Oversee NRRSTP policy, implementation, and evaluation.

Publish quarterly public dashboards on installations, costs, savings, and resilience outcomes.

Enforce anti-monopoly and anti-billioneering safeguards, including caps on market concentration and disclosure of beneficiary data.

Coordinate with disaster preparedness agencies to embed solar into national resilience planning.

Anti-Billioneering Guardrails

To maintain legitimacy and public trust, the programme will:

Prohibit exclusivity contracts or discretionary licensing.

Publish all procurement and subsidy data.

Cap installer market share under the programme.

Mandate conflict-of-interest declarations for officials and vendors.

Renewable energy must not become another extractive frontier.

IMAGE 1: Administrative Map of Jamaica, W.I. & IMAGE 2: A Global Horizontal Irradiation (GHI) map showing the total amount of solar energy hitting flat, horizontal surfaces and others across Jamaica, combining direct sunlight and scattered light, measured in energy per area (like Wh/m² or kWh/m²) over time.

Implementation Timeline

Phase 1: Framework & Mobilisation (0–6 months)Legislation, portal development, installer certification, pilot financing agreements.

Phase 2: Pilot Rollout (6–12 months)Targeted installations in hurricane-exposed and high-cost-burden communities.

Phase 3: National Scale-Up (12–36 months)Acceleration toward 200,000 households; workforce expansion.

Phase 4: Consolidation & Review (36–60 months)Performance evaluation and planning for next-decade expansion.

NATIONAL BENEFITS

Lower household energy costs and reduced cost-of-living pressure.

Improved post-storm resilience and faster economic recovery.

Reduced fuel import bills and foreign-exchange exposure.

![Jamaica's Energy Sources Composition--depicts the change from 2009 to 2015. Currently, Jamaica depends heavily on petroleum imports to meet its energy requirements since it lacks fossil fuel deposits. At least 93% of the population has access to electricity supported by petroleum. Nevertheless, the island faces an increasing demand for fuel and the scarcity of financial resources to cover an increased oil bill, limiting energy security since approximately 9 to 11% of its gross domestic product covers oil imports [2]. As a result, the benefits of transitioning from fossil fuels toward renewables extend beyond increased energy security. Comparative cost assessments show that, by 2030, Jamaica can save up to USD 12.5 billion in energy system expenditure [3]. Accordingly, the negative environmental and economic repercussions demand a shift from fossil fuels to varying RE options. The share of RE sources in Jamaica has increased from 9% in 2009 to 19% in 2020, as shown in the above image. This energy is derived from renewable sources such as wind, mini-hydro, biomass, and solar power. Nonetheless, the government of Jamaica seeks to reduce energy imports from 81% to 50% by 2030, as cited by the Ministry of Energy and Mining [4], the Prime Minister’s Office [5], and the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), 2021, in ENERGY PROFILE Jamaica. CREDIT: Delmaria Richards, Graduate School of Science, Technology, Information Sciences, Tsukuba University, Japan and Helmut Yabar, Graduate School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Tsukuba University, Japan](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/331ac9_5364554985054f17a4a29e23c245d959~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_550,h_221,al_c,q_80,enc_avif,quality_auto/331ac9_5364554985054f17a4a29e23c245d959~mv2.jpg)

Job creation and skills development across all parishes.

Restored public confidence through transparent, equitable delivery.

© Dennis A. Minott, PhD. All rights reserved.

No part of this document may be reproduced, stored, transmitted, or adapted in any form without prior written permission of the author, except for brief quotations with full attribution.

Conclusion

This proposal offers Jamaica a credible path to solar democracy: one that strengthens resilience, lowers costs, and restores trust. It is ambitious yet practical; transformative yet disciplined. Most importantly, it is designed for Jamaica as it is now, not for an abstract future.

The choice is not whether Jamaica will decentralise its energy system—but whether it will do so wisely, fairly, and in the public interest.

by Dennis A. Minott, PhD.

ENERPLAN Verde Siempre Group

Email: a_quest57@yahoo.com

January 8, 2026

%202021_edited_edited.jpg)

Comments